Originally Published by Our State Magazine and written by Phillip Gerard.

The 1960s: The Fast Cars and Outlaw Heroes of NASCAR

Thanks to the grit of its drivers and the thrill of its events, the sport started by moonshiners shifts into high gear. Born on the dirt tracks of the North Carolina Piedmont, stock car racing becomes a national pastime.

North Wilkesboro Speedway — one of the original NASCAR tracks — was home turf for Junior Johnson, the “Wilkes County Wildman,” who took the checkered flag in this 1965 race.

photographby RacingOne/ISC Archives/Getty Images

The lore of the “Dixie Dynamo” gets a high-octane boost in March 1965, when Esquire magazine publishes Tom Wolfe’s breathless ode to a stock car racer from Wilkes County, the moonshine capital of the state: “The Last American Hero Is Junior Johnson. Yes!” Wolfe is one of a handful of self-styled “New Journalists” who are reinventing the genre of nonfiction reportage in personal, often overheated prose.

The subtitle says it all: Johnson “is a coon hunter, a rich man, an ex-whiskey runner, a good old boy who hard-charges stock cars at 175 m.p.h. Mother dog! He is the lead-footed chicken farmer from Ronda, the true vision of the New South.”

There are plenty of amazing drivers who careen around oval dirt tracks at ungodly speeds, barely under control — sometimes losing control, hitting each other, hitting guard rails, their numbered cars flipping and catapulting clean off the track. Among them are Larry Wallace, Hank Thomas, Ralph Earnhardt, Jimmie Lewallen, and the father-son team of Lee and Richard Petty — the former a three-time NASCAR Grand National winner, the latter the 1959 Rookie of the Year who will go on to rack up 200 career wins.

But Junior Johnson is the perfect front man for a sport that embodies far more than the thrill of reckless speed. Every race carries outlaw history and deep cultural roots, and Johnson can rightly claim his part in both.

Racing also carries the risk of catastrophe in every lap. Fans don’t watch an NFL game expecting a football player to launch himself out of bounds and burst into flame, but every NASCAR race holds the potential for such crashes. Drivers routinely bump and nudge each other’s cars — “trading paint,” in the argot of racing — to gain an advantage. Drivers often style themselves as rebels, and in the early days, some even keep a flask of whiskey in the car. And every driver’s pit crew tries to gain an edge — pushing the rules as far as they can, cheating as long as they can get away with it. As Johnson tells it, “Cheat on everything, the rules that they had. Cheat on ’em and try to get advantage. They call it cheatin’, but it’s just getting advantage on ’em.”

Stock car racing began as a series of weekend contests among whiskey drivers on makeshift dirt tracks for friendly wagers and bragging rights. The North Carolina Piedmont — encompassing Charlotte, North Wilkesboro, Winston-Salem, and Greensboro — has long been considered the birthplace of the sport. Now, it has become organized under the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR), which sanctions a series of races all over the country that carry heavy purses and points toward a national championship.

Robert Glenn “Junior” Johnson is the son of a moonshiner, a veteran of Thunder Road. Starting as a teenager, he delivered untaxed white lightning in a 1940 Ford Deluxe Coupe, 130 gallons per run, riding on beefed-up custom suspension along snaky mountain roads into the cities to slake the local thirst. His father was busted by federal revenuers with the most moonshine they’d ever seized during a raid in North Carolina. Junior took over the business and had 35 still hands and drivers on his payroll, operating not just souped-up cars but also 10 freight trucks and two tractor trailers — before earning his own stint at Chillicothe federal penitentiary in Ohio.

Years of running moonshine on the back roads of Wilkes County prepared Junior Johnson for NASCAR tracks — dirt and asphalt alike. photograph by RacingOne/ISC Archives/Getty Images

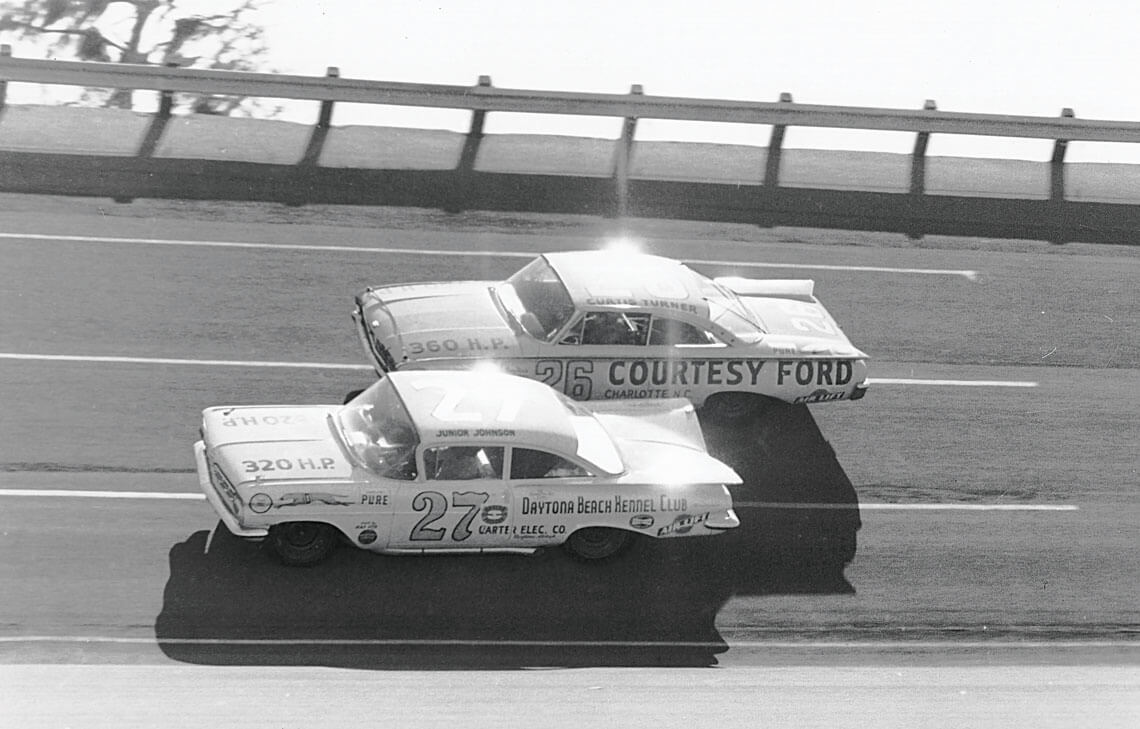

He is both ordinary — good-looking but not movie-star handsome, amiable but not charismatic, famous but also shy of strangers, eloquent (especially about cars) but not given to small talk — and extraordinary: By the time Wolfe’s national article appears, Johnson, just 33, has already won 37 NASCAR races (out of 50 career wins). During the 1960 Daytona 500, he uses his self-invented technique — drafting his underpowered ’59 Chevy in the slipstreams behind the lead cars, then slingshotting ahead — to beat out a field of 67 competitors for a surprise $19,600 victory. Unlike many other drivers, he races not to accumulate seasonal points but only to win.

Johnson speaks of his racing with a kind of calm detachment. “You’d think you’d get excited if you was running at 150 or -60 mile an hour, and move on up to 175. But like down at Daytona … I took my car out and just tried it out and just put it wide open. And they had clocks at every turn in different places, and when I come in, they said, ‘How fast d’you think you run?’ I says, ‘A hundred and eighty.’ And they said on the back stretch, I run 230 mile an hour.”

Johnson is a veteran of Thunder Road who delivered untaxed white lightning, 130 gallons per run.

Like many other drivers, such as Banjo Matthews and the Pettys, Johnson is also an expert mechanic, trained on all those whiskey cars in the arts of suspension, brake setup, and engine-boosting.

The racing circuit that has become NASCAR began on dirt tracks, on which the cars competed in a kind of permanent skid. Johnson puts it this way in a 1988 interview with historian Pete Daniel: “You broadside a car quite a bit when you’re running dirt.” Winning on the asphalt track of Daytona marks Johnson as a figure who can bridge the old track techniques and the new ones.

•••

Unlike baseball and football, stock car racing is not mainly confined to large metro areas like New York City or San Francisco. Its roots lie in the rural counties, and dirt tracks are scraped out of pastures from the Piedmont to the coast, some of them built to last, others good for a few seasons of racing by local drivers before falling into disuse.

Wake County Speedway opens in 1962. Carolina Speedway in Gastonia offers go-kart racing in 1961 and, the next year, full-size dirt track racing. Draper Speedway in Rockingham County features pro NASCAR drivers but also an amateur division with drivers such as George “Scooter” Minter and Jesse “Single Eye” Dishman — hard to miss while wearing his eyepatch. In Asheville, racers compete on a quarter-mile track around McCormick baseball stadium. In one storied race, Banjo Matthews — legendary for his relentless driving as much as for his skills in “setting up” race cars — bumps Ralph Earnhardt’s car clear off the track and into the first-base dugout.

At the Daytona 500 on February 14, 1960, Johnson, No. 27, ducked around Curtis Turner, No. 26, and ultimately won the four-hour race. photograph by RacingOne/ISC Archives/Getty Images

At the old Charlotte Fairgrounds Speedway, Richard Petty of Level Cross finishes first in the 100-mile NASCAR Grand National event — his first big win, worth a purse of $800 for the 22-year-old driver. In 1959, O. Bruton Smith, a car dealer and racing promoter, and Curtis Turner, a lumber tycoon turned driver, build a custom asphalt “superspeedway” — Charlotte Motor Speedway — and inaugurate it in 1960 with the first running of the World 600 (now the Coca-Cola 600), intended to rival the Indianapolis 500.

As the decade comes to a close, the dirt tracks are mostly gone. The final dirt track race in the NASCAR top touring series takes place, fittingly, in the state where it all began. In 1970, the North Carolina State Fairgrounds in Raleigh hosts the Home State 200 on its half-mile oval — and local hero Richard Petty takes the checkered flag.

Wolfe has christened the new high-speed Sunday “church” of racing and names its saints: “We were all in the middle of a wild new thing, the Southern car world, and heading down the road on my way to see a breed such as sports never saw before, Southern stock-car drivers, all lined up in these two-ton mothers that go over 175 m.p.h., Fireball Roberts, Freddie Lorenzen, Ned Jarrett, Richard Petty, and — the hardest of all the hard chargers, one of the fastest automobile racing drivers in history — yes! Junior Johnson.”

NASCAR is coming into its own, with television coverage making it a national rather than just a Southern sport. Stock car racing, which began with outlaw drivers showing off their prowess on the dirt tracks of Charlotte and North Wilkesboro, High Point and Greensboro, Concord and Hillsborough, has become America’s sport.

Another Lap Around the Speedway

North Wilkesboro Speedway was built in 1946, in part to settle bets among local moonshiners who wanted to find out whose souped-up car was fastest. The 5/8-mile track was unique: Because the builders ran out of money while grading it, the front stretch was downhill, and the backstretch was uphill. The track was home to NASCAR races until it closed in 1996. Last year, Dale Earnhardt Jr. led the charge to have the storied track scanned by iRacing, and it came back to life in digital form, with NASCAR’s current stars holding a virtual race there before returning to live racing earlier this year. — Jeremy Markovich

This story was published on Jul 28, 2020

Philip Gerard

Philip Gerard is the author of 13 books, including The Last Battleground: The Civil War Comes to North Carolina. Gerard was the author of Our State’s Civil War series. He currently teaches in the department of creative writing at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. He received the 2019 North Carolina Award for Literature.